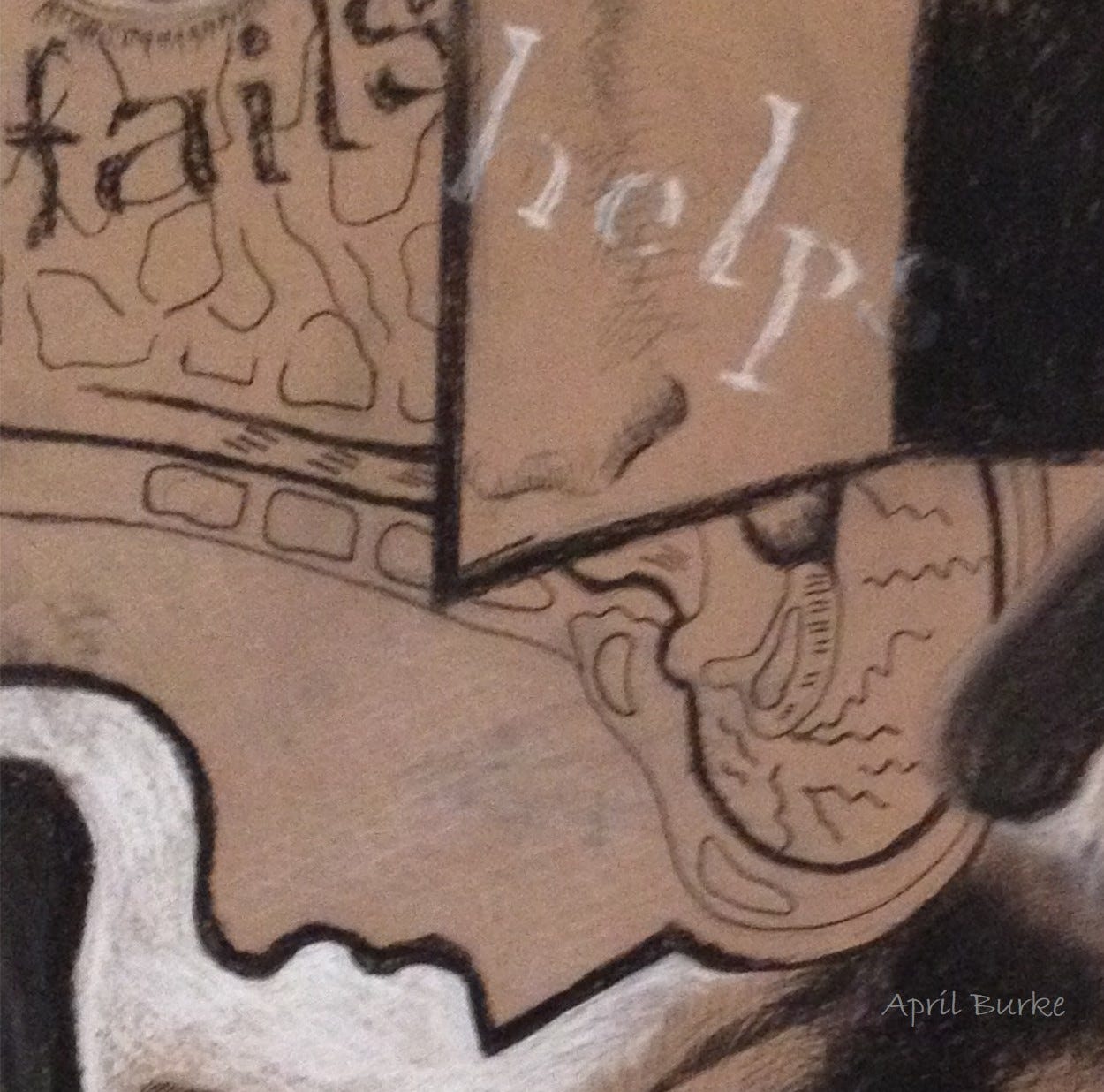

[Section of a drawing by

]How do we understand the general public response to the assassination of the UnitedHealthcare CEO?

While it’s generally agreed that murder is wrong, this case appears to have most people—spanning both sides of the political aisle—sympathizing not with the victim of the assassination but with the victims of the healthcare system he represents.

The U.S. private health insurance system is often brutally inhumane, focused on profit rather than the people it’s supposed to serve, with egregious stories that most people can relate to on a personal level, with individual friends or family having been denied coverage in dire moments of need, while insurance companies make obscene levels of profit.

In addition to the category of deaths of despair, one concept that has resurfaced in light of recent discussions of the state of healthcare in the U.S. is that of Marx’s longtime collaborator Friedrich Engels, the idea of social murder, introduced in his 1845 Conditions of the Working Class in England.

This ultimately simple concept bears relevance today, beyond the context of 19th Century England, in the light of Marx’s analysis in Capital.

Without using the term “social murder,” Marx at various points in Capital touches on and develops the same idea; or rather, he touches on dynamics of the capitalist economy that should inform the concept of social murder, as he describes the ways in which misery and death can be increased as a result of revolutions in the technical means of production, as implemented in the capitalist economy.

Here, I’ll briefly introduce Engels’ concept, and then I’ll show how Marx’s analysis informs our understanding of the way in which capitalist society continues to commit what Engels calls social murder.

A too early and an unnatural death

Writing as a young man amidst the Industrial Revolution, Engels in Conditions of the Working Class in England explains the development of labor organizations and strikes from the point of view of the workers within the social circumstances of capitalism.[1] For Engels, the proletariat’s struggle is a fight against the deterioration of the conditions of their livelihood, which would only worsen by the tendencies of capitalists acting according to their interests and the necessities of the economic system of capitalism.[2]

The passion for rebellion and revolt among the proletariat is explained by their horrid living conditions which include an imminent, early death caused by social conditions.[3] Engels considers the “physical, mental, and moral status” of the workers “under the given circumstances.” He writes:

society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet…it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence… [Society in England] has placed the workers under conditions in which they can neither retain health nor live long; that it undermines the vital force of these workers gradually, little by little, and so hurries them to the grave before their time.[4]

Engels describes the social circumstances of capitalism as causal of “social murder.” These oppressive conditions include deprivation of the working class of adequate access to “the necessaries of life” to the point at which “they can neither retain health nor live long.” Engels describes a society which “undermines the vital force” and makes “early and unnatural death” inevitable.[5]

According to Engels, “society knows how injurious such conditions are to the health and the life of the workers, and yet does nothing to improve these conditions.”[6] Thus, as Engels articulates on several occasions in the book, “[t]o escape despair, there are but two ways open to [the proletariat]; either inward and outward revolt against the bourgeoisie or drunkenness and general demoralization.”[7]

Beyond the specific conditions of the English working class of 19th Century England, Marx’s analysis in his late work Capital demonstrates, as I’ve written about previously, the ways in which exploitation can increase in capitalism independently and even simultaneously with increases in standards of living.

The misery, the sufferings, the possible death of the displaced workers

Late in Capital Vol. 1, Marx describes a revolutionizing process of the accumulation and concentration of capital, where by with the development of machinery across industries there comes a diminution in the value of labor power and an increase in unemployment: the “progressive production of a relative surplus population or industrial reserve army” of the unemployed.[8]

These “periodic changes of the industrial cycle” involve the expulsion of populations of workers from the workforce as well as the increased exploitation of those who remain employed, and “Not only are the workers directly turned out by the machines set free, but so are their future replacements in the rising generation.”[9]

Thus, there is also the immiseration and possible deaths of those expelled: “the misery, the sufferings, the possible death of the displaced workers during the transition period when they are banished into the industrial reserve army.” Wages fall as the reserve population grows, and birth rates subsequently rates fall; as the reserve army then shrinks again, wages once again rise.[10]

The process results too in divisions between employed and unemployed, whereby those employed become compelled to work more or more intensely by “the pressure of the unemployed:” “the pressure of the unemployed compels those who are employed to furnish more labour, and therefore makes the supply of labour to a certain extent independent of the supply of workers.”[11]

As soon as the workers learn how all this works—how wages and productivity are affected by the relative size of “the reserve army” of unemployed—they begin to organize, via trade unions and other organizations, to develop cooperation between employed and unemployed “in order to obviate or weaken the ruinous effects of this natural law of capitalist production on their class.” In response, “capital and its sycophant, political economy, cry out at the infringement of the ‘eternal’ and so to speak ‘sacred’ law of supply and demand. Every combination between employed and unemployed disturbs the ‘pure’ action of this law.”[12]

These kinds of concentrations of capital and subsequent intensifications of work are what lead to the working-class struggle to reduce the working day from one without limit to one of 12 hours, and then, after a relative increase in productivity (and, thus, the rate of exploitation), to reduce it again from 12 to 10 hours. Marx correctly predicted that workers would again need to fight to reduce the working day,[13] as of course in the 20th Century it was finally reduced to 8 hours, and we know we’re long overdue for another reduction; hence, the movement to push for a 4-day workweek.

Today, a lot of pain and misery remains throughout the economy in a situation which should be understood not only within the context of the pandemic but of the neoliberal era of capitalism and the Great Recession in which that era largely culminated, a problem handled with bank bailouts and foreclosures of millions of working-class people’s homes.

When capital is re-accelerated through displacements of workers via some revolution in the means of production—for example, the mass movement of factories to other countries, or by introducing increased levels of automation—misery and deaths of despair in society increases, not only for the workers directly displaced but also for the rising generation, while productivity for those who remain within the workforce becomes increased and more exploitative.

These kinds of deaths, caused by the circumstances of the economy, are a damning indictment of our form of society and its priorities.

Notes

[1]. Friedrich Engels, Conditions of the Working Class in England, (2005 [1845]), trans. by Mrs. F Kelley-Wischnewetzky (London: Penguin Books, 2005), 148, 225-226.

[2]. Ibid, 223, 227-228.

[3]. Ibid, 127-128.

[4]. Ibid, 127-128, [italics original]

[5]. Ibid.

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. Ibid, 163.

[8]. Marx, Capital: Vol. One (1990 [1867]). trans. by Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin Books), 781-94.

[9]. Ibid, 792.

[10]. Ibid, 793.

[11]. Ibid.

[12]. Ibid, 793-4

[13]. Ibid, 542.